On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City. The storm arrived with an unprecedented intensity due to high tide on the Atlantic Ocean and by extension, New York Harbor. The night of Hurricane Sandy’s arrival was during a “spring” tide, a weather phenomenon where the moon is full and the tide reaches its monthly peak. By the time Sandy made landfall, it was more than three times the size of Hurricane Katrina. The southern coastline of New York was battered by record-breaking storm surges, countless residents were displaced due to the storm, critical infrastructure was destroyed. Video clips of Lower Manhattan submerged underwater, rapids forming in the streets between buildings, still stay with me to this day.

When Hurricane Sandy hit our coastline, I was sixteen years old and was growing up in a town located less than twenty-two miles from Midtown Manhattan. I remember losing power for over a week as the weather began to turn colder. I remember being out of school for a week. I remember the lines of cars idled at gas stations stretching on for miles. Forty-three New Yorkers died as a result of this storm. This devastating storm was my first exposure to the stark reality of living in a world with a rapidly changing climate. At sixteen, I began to think about what it would mean to live in this world– and the massive, existential question of bringing new life into it.

Just over a year after Hurricane Sandy made landfall, I began dating for the first time. It pains me to discuss the details surrounding why I was dating during a difficult childhood where I was, in essence, an adult long before I needed to be– but this felt like the “next step” in growing up (and as referenced in a previous essay, a means of building deeper emotional bonds with friends of mine who were girls). During the time period between the end of high school and beginning of college, I was sexually assaulted for the first time. I was young, impressionable, and scared– all of which made me an easy target for older men to take advantage of me. I was unable to turn to my parents about this assault; I was alone in these feelings.

Instead of talking about the deep shame and fear I felt all over my body for years after the fact, I compartmentalized it inside of me– thinking I could eventually unpack that box when I was older and with a so-called sense of strength and independence. I was terrified that I was pregnant (I was not), and kept buying and hiding pregnancy tests for months after the assault occurred. It wasn’t until I very briefly moved upstate to work on a small-scale biodynamic farm that I realized the stress was pouring out of me in the form of panic. I was living in a house owned by the two farmers, with only myself and one of their other farmhands– a soft-spoken and shy, but grown man. Although he was only kind to me and did not do anything wrong, I was in a near-constant state of fear and panic around him. Despite enjoying the work, I left the farm early.

By the time I arrived at my Historically Women’s College, I felt a safety I had not felt prior to my assault. I began to think about the events I had experienced during my childhood now that I was in a safer place: How were Hurricane Sandy and my sexual assault intertwined in my personal life? When I look at my life from a birds-eye view, how do I want to experience the landscape of it? My life was becoming imbued with incredible feminist, queer, and affect theory that colored my worldview– and still do to this very day. I began to make greater sense of my life in a way that was shimmering with options I did not know existed until I went to school. For the first time, I saw life as something that was not just a singular “mine” to live-- but a vast, living quilt of responsibility which included myself, as well as those with which I was in vague and close senses of community. As I continued to patch this ever-growing quilt together throughout the years, it was becoming clearer and clearer that biological children were not a part of the life I saw for myself.

I began to research tubal ligation procedures. I remember going on numerous forums to scroll through the opinions of people who have had the procedure done– a repeated action I would take as I fantasized about the day I could have it done, too. There were a million reasons I was constantly dissuaded from it by family and medical professionals alike: I was too young, too ignorant, too uninformed about how I would surely “change my mind” and suddenly yearn to become a mother– a label that I could never imagine being tacked on to my nuanced and gender-expansive identity. There are so many more things I wanted to be, and still want to be– I would love to be a meaningful and safe part of a child’s life one day, but that child will not be “mine” in a biological sense. One of the only people who I could have purposeful conversations with about this was my college thesis advisor, Christian Gundermann. He was one of the few adults I could speak to in a very candid way about my fear for this rapidly changing world. We spoke about everything– from the reactionary, populist right-wing political shift our world is undergoing, to the ever-increasing devastation climate change will continue to wreak upon all facets of life on Earth. I felt validated in the fear and hope I had for our world. As much as I want to continue living, I could neither justify nor push myself to feel any desire to bring new life on Earth from my own body. Although there are thousands of reasons for starting a family– for myself, I cannot find one.

Then, on June 24, 2022, a massive blow came to the right for bodily autonomy in a way that directly impacted my future in this country. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned 50 years of precedent, overruling Roe v. Wade– eliminating federal protection for the right to abortion. I remember receiving the news at work; I remember being catatonic for the rest of the day. I couldn’t stop thinking about my terrified teenage self, the young Emma who was so alone after having the unimaginable happen to them. I thought back to the conversations I had with Christian, knowing that my protections back home in New York State were superficial in the face of what could very well happen down the road amidst the rising tide of rightwing extremist legislation and judicial rulings. I knew I wanted to move forward with my life in one overwhelmingly clear direction: that if the unimaginable happened again, I could still hold on to some semblance of the normalcy and independence I crave from this life. Later that summer, I scheduled an appointment with my gynecologist to begin discussing my tubal ligation.

After multiple appointments and stern discussions where I was challenged to recount all of the reasons why I do not ever see myself having biological children, I was presented with an offer for a bilateral salpingectomy procedure in early 2023.

By the evening of March 30, 2023, the procedure was complete. I woke up in a recovery room in the Women’s Hospital surrounded by kind nurses who pushed the Zofran I gingerly requested into my IV as I rode out waves of post-anesthesia nausea. I remember loopily talking to the nurses for over an hour about how the c-suite admin at hospitals don’t understand how hard they work– I laid on thick how much I supported their union. Three of my best friends were waiting for me as I was wheeled down by one of the nurses. I got to experience the first night of my life as a permanently sterilized person among my dearest friends who supported me in this choice.

As I am writing this essay in late July of 2023, I believe having my bilateral salpingectomy was one of the greatest acts of love for myself, and the ever-growing patchwork of experience that is forever becoming my life. I understand my sterilization as a step towards deep adaptation– a concept and social movement of taking strong personal and cultural measures to adapt to the near and long-term social collapse of Western industrial lifestyles due to climate change. Deep adaptation presents a system of adaptation that relies on a framework of constructive action in order to cope with rapidly accelerating climate collapse. This system includes the (inter)personal actions of curiosity, respect, and compassion. My first practice of compassion within the context of deep adaptation was in my bilateral salpingectomy– a compassion towards myself and towards the future of children living in a country with woefully inadequate infrastructure to cope with accelerating climate collapse. By not bringing a biological child of my own into the world, I can engage with the precautionary principle in a highly localized way. I can make myself more available to engaging with the world as I hope to– with respect, curiosity, and compassion towards myself, my loved ones, and those I am in a broader sense of community with.

From October 29, 2012 to July 2023, our world is different. Antarctica failed to replenish its winter sea ice this year, leading to what some scientists are calling a “five sigma event” of climate change. The new rightwing Italian government, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, has begun moving forward with the “traditional family-first” legislation that recently passed. This includes removing the names of non-biological lesbian mothers from their children’s birth certificates. It is hard and frightening to say where we go from here. Anyone would be scared. Anyone would hold onto a glimmer of hope that things can still change for the better.

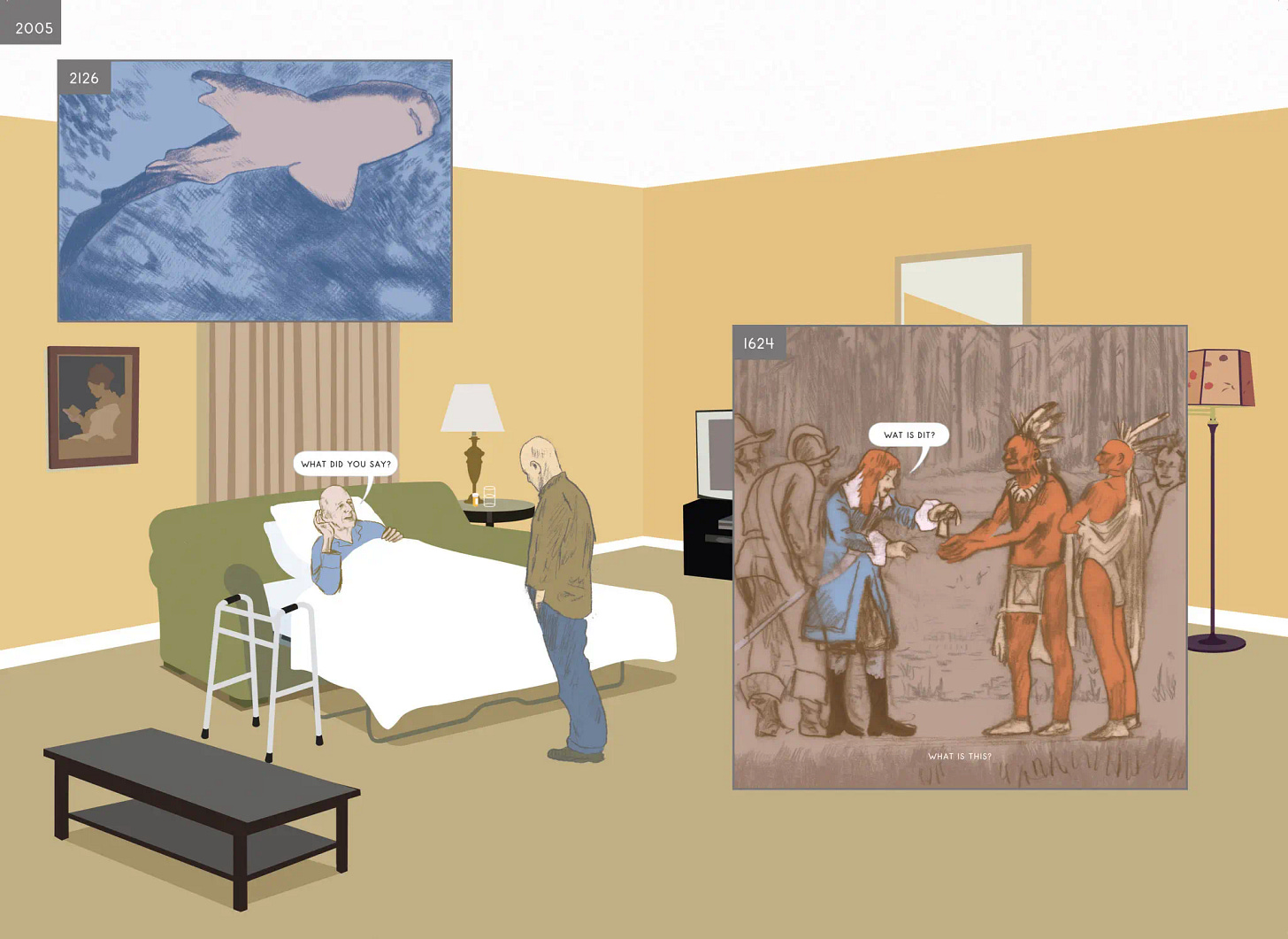

In one of my favorite graphic novels, Here by Richard Mcguire, the main character is a static location: sometimes a seam where two walls meet, at other times a deep past forest, or a future ocean, as the ages pass. As you turn the pages, time moves backwards and forwards and is often mashed together in ways that make the enormity of deep time easier to understand. It is not unusual to to see a frame of a room from 1951 overlaid with another frame from 1726, a massive bison sitting next to two men having a conversation, unbeknownst to either of them. They cannot see each other through time, but we, as the reader can. I sit here, in an apartment in New York City and write this essay– wondering if there are rising waters teeming with new life above my head one-hundred years in the future that I cannot yet know. There are so many futures I will never know. I know in the immediate present, right now, I am grateful to have authority over my body. I can meet this world with grace and love for myself, for others I know, for others I will never know.

(While I am discussing my procedure in a celebratory tone, there is no doubt that the United States has a horrific and storied history with involuntary sterilization as a method of eugenicist violence. Although I will not go into further discussion in this essay of how the United States has utilized tubal ligation as a violent tactic of control among a multitude of marginalized populations, I do want to provide the link to an important documentary about the recent history of tubal ligation when it is practiced in a eugenicist context.)

Emma, this is a very interesting assay, which not only raised a few questions in me---perhaps once in person I will ask them---but also revealed some generational differences between you, a gen-Z-er and me, a gen-X-er. Looking forward to seeing how your essays evolve in the future.